Bettie Page, boarding school, living up to the family name, working for Sotheby’s in New York, entering the world of burlesque queens and meeting Zorita the QUEEN of them all..

As a kid I was insatiably curious about sex, stealing my dad’s Playboy magazines and asking for more details than any adult wanted to share. When traveling with my parents on Dad’s work trips to New York as a little girl, I was often left alone in a hotel room while they were out doing adult things and it was there I discovered public access television. My favorite cable star was Robin Byrd, who had her own show where she would appear topless or fully nude, interviewing strippers and porn stars. It was riveting and not at all what a 9 year old should be watching. But it explains a lot about where I ended up.

In high school, I got serious about photography, shooting arty nude portraits of my friends. My first subjects were my girlfriends, but then I went into a head trip about needing to confront my double standard of nudity. I wanted to know more about the mystery of sex and why it was so powerful but I also wanted to have control over how and when I encountered it. So I decided to get comfortable with shooting men. In my dorm room. At 15. My mind is blown now wondering how no adult or teacher said anything to me about coming into photo crit class with hand printed black and white images of penises. That belonged to high school students. I wasn’t actually comfortable with them (the penises, that is) in person. I hadn’t had penetrative sex yet, but somehow through the lens of my dad’s 1940s Nikon camera, it was safe.

The boys who posed for me posed no threat— they were progressive, sensitive, and comfortable with their sexuality, whether straight or queer identified. My boarding school was the first high school in America to have a gay-straight alliance, formed by my history teacher, Kevin Jennings, in the decade before I attended. Many of my classmates were experimenting with sexual and gender preferences and expressing their experiences in front of the entire student body during “chapel,” a Quaker-style morning meeting held in the Colonial era chapel on campus. On the flip side to this freedom of expression, was a whole other set of boys, back in LA and on campus, who clung to a version of masculinity that denied them vulnerability, fluidity or communication.

My friends and I had plenty of shared experiences of boys wordlessly pushing our heads down to their crotch indicating they wanted a blow job without any conversation around what our boundaries or mutual desires were. Even at my liberal high school, during study hall a couple of senior lacrosse jocks would regularly come around to us younger girls desks and pretend to talk, waiting until we looked down and noticed their flaccid dick was brushing up against our textbooks. This was a couple decades before #MeToo and TikToks featuring confident young women sharing tips for dealing with pervy Uber drivers. I helped start a rape & sexual assault support group on campus but we definitely didn’t discuss date rape publicly. There wasn’t much you could do about sexual harassment, except to deflect or pretend to laugh if off. If you weren’t in on the joke or came off like an “angry feminist” they would just make your life worse. You were a bitch, slut or a good girl. So you sucked it up, repressing and suppressing all the rage, pain, and betrayal you might be feeling. Like our mothers did, and theirs and theirs and so on.

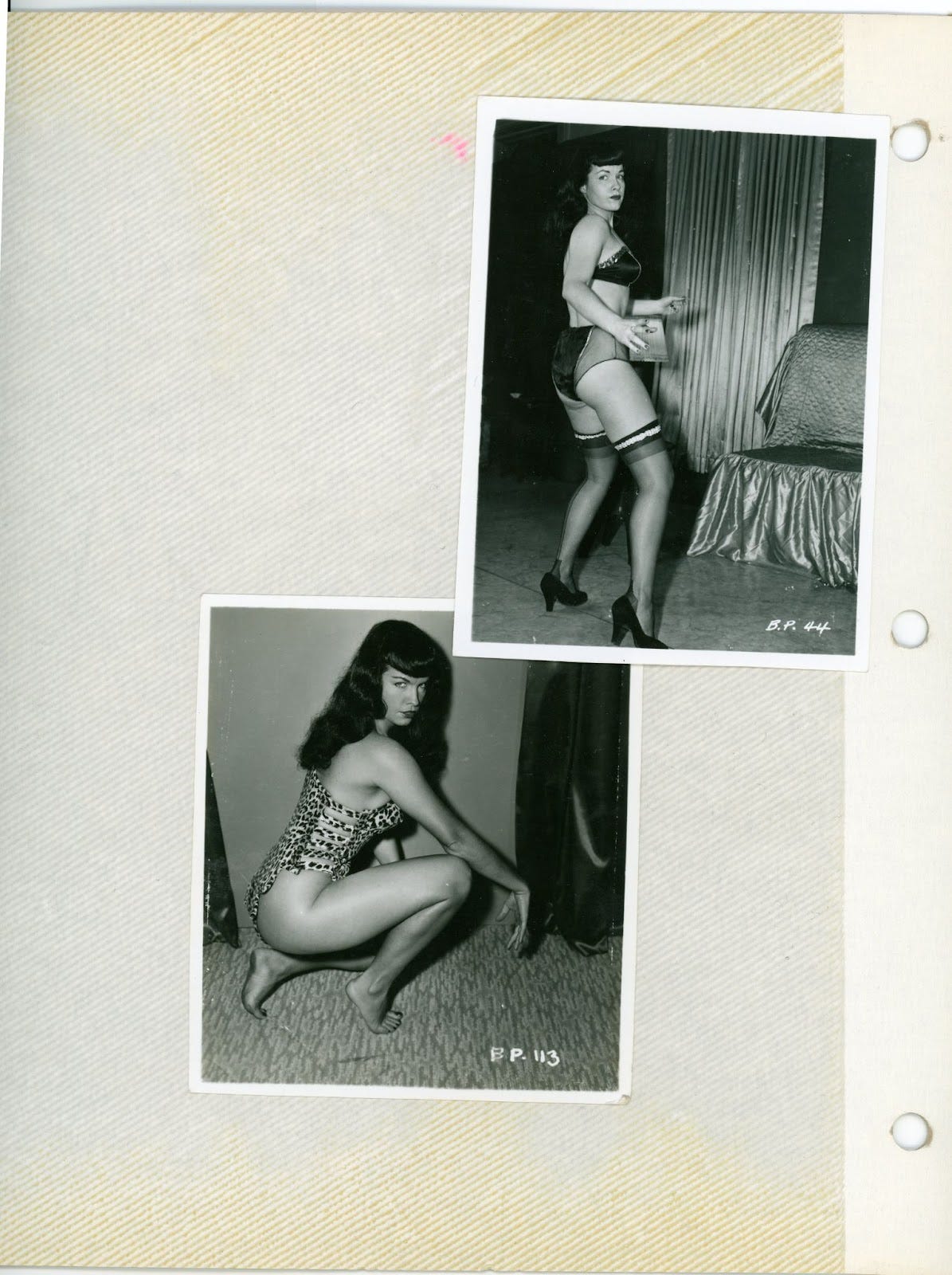

While I was trying to sort out my own feelings around sex, I was collecting old pinup photos, in thrift stores and flea markets—black and white images of Bettie Page looking seductive in leopard print and black leather, posing on carpet and against wood paneling. To me, she radiated confidence, strength and desirability—qualities I wanted to possess. The kind of woman who would know exactly what to say to put boundary-crossing boys in their place.

Instead of adults asking about my college plans or life dreams, there were repeated questions that felt more like statements: you’re obviously going to be in the movie business like your family; when are you going to make a movie? Are you going to be an actress? Following in my family footsteps was the furthest from my mind. The pressure of having to live up to the name plus the handicap of my gender in an industry where boys club was a serious understatement was too daunting. A good percent of my boarding school friend’s parents were professors and I thought that was the most glamorous occupation someone could have. A Ph.D seemed much more attainable than an Oscar and more validating, as it wasn’t based on popularity or industry connections. I remember one of my closest friends' mom, a Harvard professor, telling me it took 10 years to become an expert in a subject, and that it was important to know when to stop and publish your research.

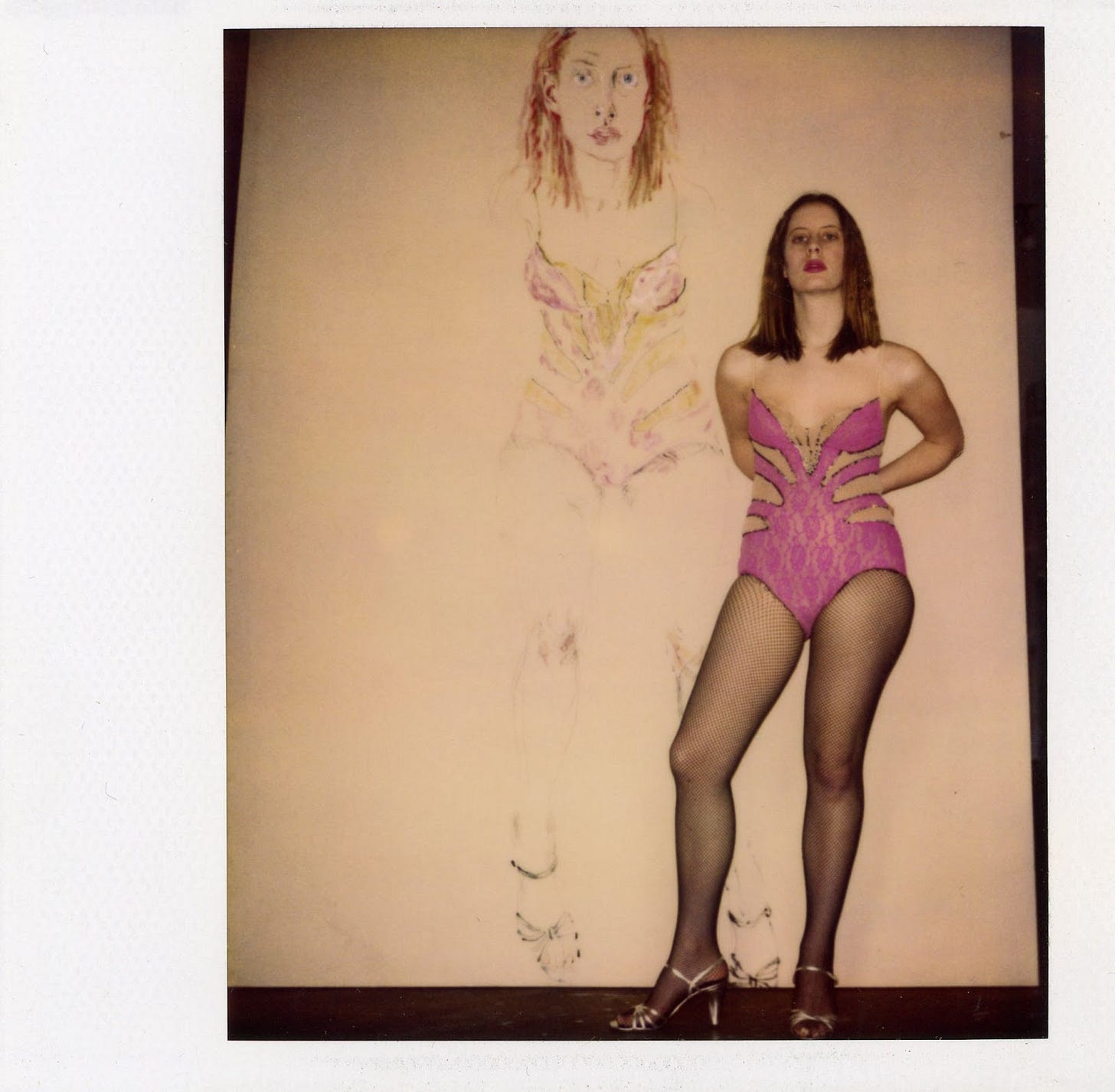

When I moved to New York to attend School of Visual Arts as a photography major, my Bettie Page obsession had evolved into collecting pinups of burlesque striptease queens of the 1930s and 40s, like Lily St. Cyr and Gypsy Rose Lee. I simultaneously discovered two 1940s burlesque costumes at a flea market which inspired me to start a self-portrait series for my thesis class. Wearing these old costumes, I attempted to emulate the poses of the pinups I was inspired by. I failed miserably, looking like an art school girl playing dress up. Still, I was undeterred. I needed to unlock the mystery of their allure and understand what had happened to these legends who emanated self assured sex appeal from their fading 8 x10s.

In my first year of art school, I started working for Sotheby’s auction house in the newly created Fashion department. We did high end vintage sales and celebrity estates that included clothing, like Marlene Dietrich and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. Due to my proximity to worldwide dealers and museums, as I was researching the burlesque costumes, I found that there was no definitive book or museum archive dedicated to burlesque queens and their wardrobe.

I became committed to tracking down and writing letters to the last surviving 20th century American burlesque queens and recording their first-person stories. I spent time at their homes, businesses and hospital rooms at the end of their lives, learning first-hand the lost art of burlesque as they dressed me in their old costumes and taught me trademark moves. Some of the queens wanted to be in showbiz, burlesque was just a starting place that they’d become trapped in. Once a stripper, society makes it hard for you to forget, then and now. These women, now in their 70s and 80s, became close friends and mentors. They came from different experiences and backgrounds—some had tight knit families, some were mothers, some had stage mothers, some had escaped abuse, some tricked for extra cash. They all had a lot to tell me about men, sex and how stripping for an audience affected their psyche. I may have been a young married woman then, but I truly had my first sexual awakening via 80-year-old strippers passing down their hard-earned wisdom to me.

The key to a burlesque queen’s enduring potency is the element of tease—the audience can look but cannot touch. Zorita, one of the queens I was closest to, invented the “half man/ half woman” act and did a striptease with two 8- foot long pythons. She was an icon onstage for generations of men, but offstage, was openly lesbian since the 1930s. That didn’t stop her from having three ex husbands. She told me that it was part of the fun to give “everybody a hard on and they can’t have it” and that I should be flattered to think I, too, could have the power to give them a “hard on”. She said she found out at an early age that “sex could be paid for. And so you give them a peek, you give them a flash, you give them a smell but you don't give it all.”

I think about Zorita often, as I reconsider how I (we) are shaped by our formative experiences — the good and the ugly— which often become the bitterness and scars we carry and pass on generationally. So much of adulthood seems to be sorting out what belongs to someone else's history. When I first met Zorita, I was a naive 22 year old married woman searching to find her identity. Years later, I am still unraveling the events that shaped me, making sense of and letting go of stories I told myself were real, based on other people’s lens of experience.

MORE ON BOARDING SCHOOL…..

Taylor Swift bought my childhood home, Part 1

Which sounds like something I’m sharing for clickbait but it’s actually true (you can google it.) Taylor is the first person to own and live in the home outside of three generations of my family. This unusual detail of my backstory used to be a source of self-consciousness— not Taylor purchasing the house—but that I grew up in a mansion suited to the li…

MORE ON COLLECTING CLOTHES & SOTHEBY’S….

It's All About Timing

My grandad was responsible for the first appearance of haute couture in cinema and was the only mogul put a famous fashion designer, Coco Chanel, under contract. But like many of my grandfather’s expensive tastes for “high brow” fashion, literature and art, it was a bit ahead of the curve. Grandpa Sam was always surrounding himself with artistic and int…

Fab. Hooked.